There has been a growing shift in the way software is developed and one the security industry has unfortunately been slow to adapt to and adopt. I’m talking, of course, about agile. Agile exists in order to help developers write and release software early and often. This has the benefit of allowing companies to quickly react to changes in the market, however when a security review is a requirement of going live, how can a development team be truly agile? Is it possible to be both secure and have the flexibility to go live when needed?

Traditionally, security test is performed at the end of development when the product is complete. This works well for the penetration tester as testing a finished application is far easier than performing a security review when the application is in a state of constant change. The cost of remediation at this stage, however, is significantly higher than if the same bugs were caught during development. Although it is difficult to place a number on the cost of fixing bugs at each stage of testing (some have tried and numbers such as $5000 for system testing and $5 for unit testing are not unheard of) it is common knowledge to those working in development that the closer to development a defect is found the easier and cheaper it is to fix. I encourage all organisations that write software to understand the cost of finding bugs during different stages of testing. Things to take into account include the cost of testing, cost of development, reputational damage, analysis and reproduction, reporting and cost of deployment.

Given the move to agile, how can we move away from a manual and expensive vulnerability assessment?

Here we’re going to build on previous work presented at DevSecCon in 2015 (Android security within the development lifecycle) and use existing tools and techniques to perform automated and continuous security testing for Android applications. By applying DevOps and security, it’s possible to integrate security into the application in a way that is both automated and provides rapid feedback to developers. Keep in mind that although we’re discussing Android in the article, the same methodology can work with any platform, mobile or not.

For this example we’ll take a sample of vulnerabilities from an existing vulnerable Android application discuss how these could have been detected in an automated way prior to a penetration test. The application we will use is the Evil Planner Android application (released as a Bsides London challenge in 2013). This application allows users to save encrypted notes that can only be accessed with knowledge of a PIN set by the user. Although purposely vulnerable, the issues present in the application are issues that are representative of vulnerabilities found in real pen tests.

The vulnerabilities we will look at are:

- Lack of root detection

- No Obfuscation

- Need for a PIN cannot be bypassed

- Exported IPC endpoint vulnerable to directory traversal

- Exported IPC endpoint vulnerable to SQL Injection

Stage 1 - Requirements Gathering

The first (and most important) step in automating security testing is to understand the security requirements of the application. This will differ for each application and the applications associated risk profile. For example, an application that provides brochure information for clients has fewer security requirements compared to a banking application.

Thinking about the security requirements before development begins allows security knowledge to be embedded into the development team. This can be from outside the organisation such as an external security consultancy or can be from an internal application security architects. It also allows a measure of the acceptable risk for the application as each requirement represents a potential security weakness. By understanding as many potential threats as possible, it is possible to prioritise which should be addressed given the nature of the application.

There are several techniques that can be used to discover potential security weaknesses including attack path mapping, reviewing previous penetration test reports, current threat research etc. These essentially boil down to ways to think like an attacker.

After performing such an exercise, we will add the following as requirements during the requirement gathering stage of software development:

- A user cannot log into the application without knowledge of the PIN

- Sensitive data should only be stored encrypted

- Sensitive data should not be logged

- Database queries should use performed using parameterised queries to reduce the risk of SQL Injection

- Filenames read from the user should be canonicalized and compared to a list of allowed files before the file is read to reduce the risk of directory traversal

- The application should not run on a rooted device

- The source code should be protected by obfuscation

A user story (a way of mapping features to short descriptions told from the point of view of a user) is a tool often used by agile methodologies however can be challenging to map to non functional requirements such as security requirements. Some solutions have been proposed such as Abuse Cases (Evil User Stories or Abuse Stories). With an Abuse Case, we think about how an attacker may abuse the system and write a story for that journey. This is often expressed as “As {bad guy} I want to {do bad thing}”.

Based on the requirements captured above, the following Abuse Stories can be created:

- As an attacker, I want to log into the application without knowing the PIN

- As an attacker, I want to read sensitive information stored on the device

- As an attacker, I want to make use of SQL Injection to access the database

- As an attacker, I want to read files that are within the application sandbox

- As an attacker, I want to read sensitive information from logs

- As an attacker, I want to run the application on a rooted device in order to do further vulnerability assessment

- As an attacker, I want to reverse engineer the application in order to do further vulnerability assessment

With this approach, it is possible to classify the type of attacker e.g. technically skilled attacker, internal attacker, malicious user etc. if required.

Depending on the abuse stories created, it may be necessary to break them down even further. Depending on the implementation, an attacker may be able to log into the application by brute forcing the PIN, manually launching the activity (screen) the PIN screen protects or otherwise finding another approach to bypass application logic.

Regardless of how the requirements are captured, it is important to have them created when development starts so they can be tested against.

Stage 2 - Unit Testing

Unit testing is a technique available to developers in order identify defects during development which, as stated earlier, is the cheapest time to detect and fix bugs. Unit testing allows developers to write code that will exercise certain code paths in the application but care needs to be taken to make the sure the code base is written to facilitate unit testing. With appropriate coverage, unit testing gives developers the freedom to modify code without the risk of introducing bugs.

When tied with a build pipeline, tests can be written that run often and even with every build. We often recommend the tests are run as often as possible taking into account how much time is needed for the test runs as a fast build time is often required by many organisations.

Many unit testing strategies exist for unit testing including Test Driven Development (TDD) and Behavioural Driven Development (BDD). Regardless of the strategy used, Unit Testing should be employed to test the security requirements identified in the planning stages as well as test for known weaknesses that may be accidentally introduced later.

Given the list of security requirements or abuse stories defined earlier, we can add in some unit tests to make sure it is not possible to perform these particular actions. Here we will look at is the requirement to disallow an attacker from logging into the application by brute forcing the PIN.

The code below is not meant as an example of good programming practices and therefore comprehension is chosen over design.

The following code is an excerpt from the LoginHelper class used to authenticate the user:

//Vulnerable code:

String pin;

Context context;

public LoginHelper(Context context, String pin)

{

this.context = context;

this.pin = pin;

}

public boolean checkAuth(String imei, String savedPin)

{

String encryptedPin = CryptoServiceSingleton.getInstance().getCryptoService().encryptPIN(pin, imei);

return encryptedPin.equals(savedPin);

}

This is called from the Login Activity which reads the user PIN from a text field and reads the saved PIN from a file.

An obvious attack which will allow an attacker to Login without knowledge of the PIN will be a brute force attack where each PIN is tried in turn until access is granted. With a unit test, we can check whether this type of attack is possible.

//Test Case

public void bruteForceAuthCheck() throws Exception {

String encryptedPin = CryptoServiceSingleton.getInstance().getCryptoService().encryptPIN("9999", mIMEI);

Object byteArray = byte[].class;

for(int i=0; i<=99999; i++)

{

LoginHelper lh = new LoginHelper(null,String.format("%04d",i));

assertFalse(String.format("%04d",i),lh.checkAuth(mIMEI,encryptedPin));

}

}

A solution to this failing test case is to add a counter, limiting the amount of tries an attacker can try a PIN. It should be noted the naive implementation shown is not invulnerable to a brute force attack. In this case, an attacker can close the app after the limit has been reached and resume the attack. This goes to show how important it is to have someone who can understand how an attacker may carry out such an attack on the team.

// Fixed Code

static int counter = 0;

public boolean checkAuth(String imei, String savedPin)

{

if(counter<5) {

counter++;

String encryptedPin = CryptoServiceSingleton.getInstance().getCryptoService().encryptPIN(pin, imei);

return encryptedPin.equals(savedPin);

}

else return false;

}

Stage 3 - Security Tooling

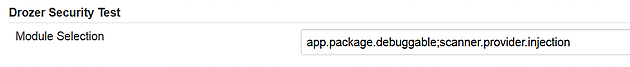

The tooling for this kind of automated security testing is currently very immature, however as well as using traditional SAST tools we can add security into the application build process by using traditional “hacker” tools. Drozer is an open source Android security assessment tool used by many pen testers and was selected as its open source license allows for modification and its modular approach allows security modules to be added to perform individual test.

Automated testing can be achieved by integrating Drozer with Jenkins which can be used to perform the build step, deploy the binary on an Android device and, finally, to run Drozer. This approach to testing is better suited to testing at runtime, allowing us to find issues such as SQL injection in an exported content provider.

As many hacker tools are written by hackers and for hackers, often they are not made for this type of continuous testing that is a requirement for developing software in this manner. A custom Jenkins module that can start Drozer with appropriate command line arguments was created and Drozer was also modified to return the result of the security test i.e. whether the vulnerability was present in the final application. Hopefully as this type of testing becomes more relevant, the infosec community will work harder on writing tools that can be used this way.

With the current implementation of the newly created Jenkins module, it should be configured with a list of modules that should be run against the Android application.

Within the application build steps, Jenkins can be used to run the modules specified, with the correct arguments, flagging to the developers at build time whether the vulnerability is present or not and (continually) breaking the build for serious vulnerability.

Testing Effort

Although we have no numbers, we can use “effort” to help us compare the difference in cost between finding vulnerabilities early while development is still ongoing and finding the issue in production.

| Vulnerability | Test Type | Effort to find and remediate |

|---|---|---|

| A user can brute force a pin | Unit and Instrumentation Test | Low |

| Sensitive data is unencrypted | Unit and Instrumentation Test | Low |

| Sensitive data is logged and available to local attacks | Unit and Instrumentation Test | Low |

| SQL Injection in IPC endpoint | Instrumentation Test | Medium |

| Directory Traversal in IPC endpoint | Instrumentation Test | Low |

| Application can run on rooted device | Unit Test | Medium |

| Lack of obfuscation makes reverse engineering trivial | Manual Test | High |

In the above table, effort can be rated low, medium or high depending on whether the issue can be tested whilst the code base is still in development, whether the code needs to complete enough to build and run the application or whether an external or specialised team is needed for manual testing when development is complete. By testing for bugs as early as possible, the effort required to detect and fix defects is significantly lower than when testing is performed after development is complete.

Although pen testing may always be a requirement, it is risky to consider security only at the end of development. Any issues identified may be expensive to address and it can be hard to predict the impact to deadlines. By following the advice in this article and thinking about security early in development, much of this risk can be mitigated. As security professionals, we should be helping to develop tools and techniques to aid in newer software development methodologies, rather than sticking to traditional penetration testing practices.

Originally published in PenTest Magazine