Jahmel Harris at Digital Interruption submitted two bugs to ToyTalk and was awarded $1750. As the issues have been resolved, he wanted to write about the vulnerabilities so other developers will take this type of attack into account when writing mobile applications.

tl;dr vuln 1 - Lack of authentication allows a malicious actor to impersonate a child talking to Thomas

tl;dr vuln 2 - Perform phishing attacks by injecting HTML into emails from support@toytalk.com

The Company

ToyTalk create “smart” children’s toys which (unsurprisingly) connect to the Internet. The reason for this is so children can have voice conversations with their toys which respond appropriately. During this research, we wanted to look at the security of these toys and understand the risks parents may be taking by bringing these types of devices into their homes. As the same library is used by all ToyTalk products, we decided to look at Thomas and Friends Talk To You Android application. As we’re very familiar with mobile testing, this seemed like a better idea than purchasing a Hello Barbie doll or Barbie Hello Dreamhouse (which would have also been vulnerable to the issues in this blog post). The Thomas app also had the advantage that the application could easily be removed after testing. We have no idea what we would do with a Wi-Fi connected Barbie when this research was over.

The App

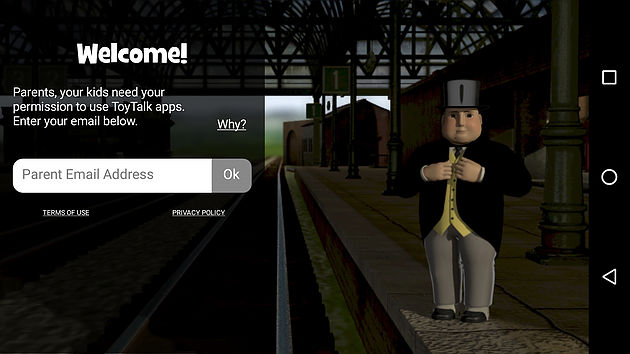

Upon startup, the application asked for an adult’s email address. This allows an adult to provide consent for their child to use the voice recognition features of the app. When an email address is provided and consent is supplied by the parent, the application starts.

Initially, it looked like the attack surface was fairly minimal for this app as the only features available were the app asking for consent and then allowing a child (or security researcher) to speak to Thomas and his friends.

The first step in most mobile application assessments is to intercept network traffic. In the case of this application, however, it proved a little more difficult than most other apps as a client certificate was in use. This meant that mutual authentication was used between the application and the web server. In that case, step 0 becomes recovering the client certificate and any passwords needed to access it.

After reverse engineering the application, it was possible to find two functions:

public void setSslClientCertificate(String filename, String passphrase) {

InputStream file = null;

try {

KeyStore store = KeyStore.getInstance("PKCS12");

file = this.mContext.getResources().getAssets().open(filename);

store.load(file, passphrase.toCharArray());

this.mClientCertificate = KeyManagerFactory.getInstance(TrustManagerFactory.getDefaultAlgorithm());

this.mClientCertificate.init(store, new char[0]);

} catch (Exception e) {

Log.OMG(e);

} finally {

Utils.close(file);

}

}

public void setSslCaCertificate(String filename, String passphrase) {

InputStream file = null;

try {

KeyStore store = KeyStore.getInstance("BKS");

file = this.mContext.getResources().getAssets().open(filename);

store.load(file, passphrase.toCharArray());

this.mCaCertificate = TrustManagerFactory.getInstance(TrustManagerFactory.getDefaultAlgorithm());

this.mCaCertificate.init(store);

} catch (Exception e) {

Log.OMG(e);

} finally {

Utils.close(file);

}

}

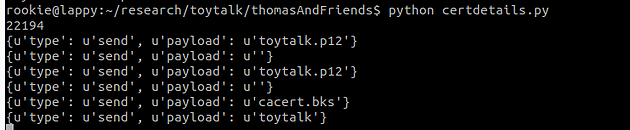

Rather than continuing to reverse the app to find where the password comes from, we used the following frida script which dumped the password and filename.

import frida

import sys

def on_message(message, data):

print message

device = frida.get_device_manager().enumerate_devices()[-1]

pid = device.spawn(["com.toytalk.thomas"])

print (pid)

session = device.attach(pid)

ss = '''

Java.perform(function () {

var MyClass = Java.use("com.toytalk.library.HttpRequester");

MyClass.setSslCaCertificate.overload("java.lang.String","java.lang.String").implementation = function(a,b){

send(a);

send(b);

return this.setSslCaCertificate.overload("java.lang.String","java.lang.String").call(this,a,b);

}

MyClass.setSslClientCertificate.overload("java.lang.String","java.lang.String").implementation = function(a,b){

send(a);

send(b);

return this.setSslCaCertificate.overload("java.lang.String","java.lang.String").call(this,a,b);

}

})

'''

script = session.create_script(ss)

script.load()

script.on('message', on_message)

device.resume(pid)

#session.detach()

sys.stdin.read()

The correct certificate files could then be extracted from the apk and used to help perform a man in the middle attack. It’s interesting to note the toytalk.12 file doesn’t use a password.

Now we’re able to use the client certificate, but we still need to bypass certificate pinning. There are several ways I can see to do this, however the easiest was to just remove the certificate from the apk, rebuild and reinstall.

With the client certificate in burpsuite and certificate pinning disabled, we can now move onto the first step of most mobile application tests - intercepting traffic.

Vuln 1 - Lack of Authentication

One feature available to the application which isn’t immediately obvious at first is that the audio files captured by the app are saved online for later playback by parents. This is tied to the email address used for consent although unavailable until a password reset is performed by the parent.

When the “speak” button is held down, the application sends the audio file in a post request to the web server as below:

https://asr.2.toytalk.com/v3/asr/0673bcb8-367a-44bc-aed5-8c21fb7086af/thomas/1502714441?account=<removed>&play_session=<removed>&client=com.toytalk.thomas&locale=en_GB&device_id=<removed>&device_model=<removed>&os=Android&os_version=5.1&intelligence=0%2F1%2Fc%2F01cd49694727bbcf1c0cefd7a4a24f2e_intelligence.tiz&ruleset_id=rs_b92dd8d9-cba9-4a76-a56b-51fc3d15f8f5&rate=16000

Although there is lots of values sent, by changing the account ID to another user’s account ID it is possible to send the audio to the specified account. This would allow a malicious actor to send obscene messages for the parent to hear.

In this case though, the account ID is a random GUID. We need a way to discover valid account IDs based on a something we might know, such as an email address.

A clue to this was actually found by running the “strings” command on the ToyTalk library.

Once the client certificate is installed in the browser, it was possible to navigate to https://api.toytalk.com/v3/account/<email address> where a file containing the account ID was downloaded. With an account ID in hand, it was possible to change the account ID in the POST request and send audio to anyone’s account given only an email address they registered with the application.

This vulnerability was fixed by requiring the correct Device ID to be submitted along with the associated account ID. We have not tested whether the device ID can be recovered, however to add a Device ID to an account, it appears that access to the associated mailbox is required.

Timeline

- Vuln submitted - Aug 14th 2017

- Closed as non issue - Nov 16th 2017

- Reopened - Nov 29th 2017

- Fixed - Dec 8th 2017

- Bounty Awarded and issues closed - Dec 18th

Vuln 2 - HTML Injection in ToyTalk email

After spending time working with ToyTalk on the previous vulnerability, Jose Lopes (@b4stiel) suggested I take another look at the register/email functionality.

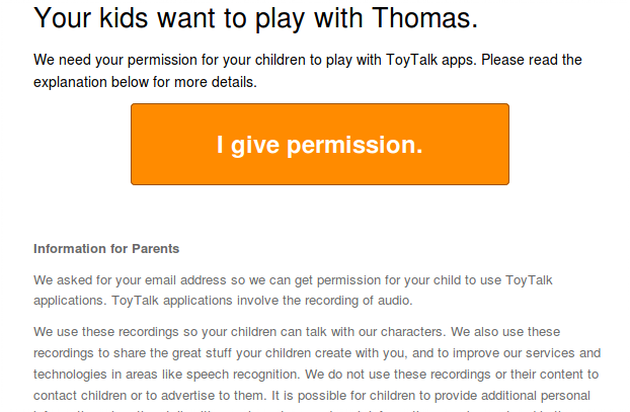

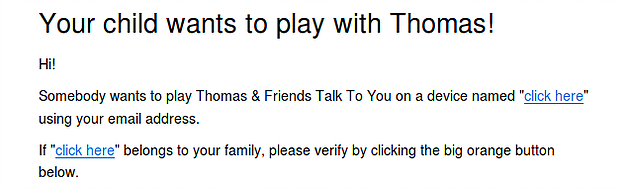

When registering a device with an application such as “Thomas And You”, an email is sent to the supplied address asking the user to confirm the device. As this email contains text from the user (the device name) it is possible to modify the device name included in the HTML of the email. This would allow and attacker to perform actions such as link to a malicious website or change the email body to be an offensive message.

To send an email to a user, the user first needs to be registered which therefore increases the likelihood of the malicious email being trusted. Using a registered email address, an attacker can recover the account ID (as discussed above) which is needed to send an email .

First, an attacker (with a victim’s email address) should make the following request to get the account ID:

GET /v3/account/<email_address> HTTP/1.1

User-Agent: Dalvik/2.1.0 (Linux; U; Android 7.1.1; ONEPLUS A3003 Build/NMF26F)

Host: api.2.toytalk.com

Connection: close

With an account ID, an email can be sent to the victim as in the following request:

POST /v3/account/<accountid>/email/consent?device_id=asdf&device_name=TEST%20DEVICE"</br>%20<a%20href="http://google.com">click%20here</a>&application=Thomas+And+You&always HTTP/1.1

Content-Type: text/plain

Content-Length: 0

User-Agent: Dalvik/2.1.0 (Linux; U; Android 7.1.1; ONEPLUS A3003 Build/NMF26F)

Host: api.2.toytalk.com

Connection: close

This is just a simple PoC that injects an HTML link using the <a> tag into an email but it is thought with some time it would be possible to craft a more enticing email to put users at risk from more advanced social engineering attacks. For example, one parent could trick another into revealing their user name/password as this email appears to come from support@toytalk.com. In the screenshot below, it can be seen we’ve added links to a malicious website in an email sent from ToyTalk.

Timeline

- Vuln submitted - Dec 4th 2017

- Acknowledged - Dec 12th 2017

- Fixed - Dec 18th 2017

- Bounty Awarded and issues closed - Dec 18th 2017